Table of Contents

Introduction: Discovering North Africa’s Indigenous People

Who are the Berbers? The Berbers, who refer to themselves as the Amazigh (plural: Imazighen), are the indigenous ethnic group of North Africa, primarily inhabiting Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and the Sahara. With a history spanning thousands of years, the Amazigh people represent one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations; their presence in North Africa predates both the Arab conquest of the 7th century and the mighty Roman Empire that once ruled the Mediterranean.

Today, as travelers journey through Morocco’s majestic landscapes, from the windswept dunes of the Sahara Desert to the snow-capped peaks of the Atlas Mountains, they walk in the footsteps of this remarkable indigenous people of North Africa. Understanding who the Berbers are is essential to truly appreciating the rich tapestry of Moroccan culture, traditions, and history that make this North African nation such a captivating destination.

The term “Berber” itself carries a complex history. Derived from the Greek word “barbaroi” (meaning “foreigner” or “barbarian”), the name was used by ancient Greeks and Romans to describe peoples whose languages they didn’t understand. While this term became widespread internationally, the people themselves have always preferred “Amazigh”, a word that translates to “Free People” or “Noble Men” in the Tamazight language. This distinction is more than semantic; it represents a reclamation of identity and a rejection of colonial terminology. Modern discourse increasingly favors “Amazigh” out of respect for this indigenous community, though both terms remain in common usage.

Etymology: Berber vs. Amazigh, Understanding the Names

The dual nomenclature surrounding the Amazigh people reflects centuries of external influence and internal identity. The term “Berber” traces its linguistic roots to the Latin “barbarus,” which the Romans borrowed from the Greek “barbaros.” In ancient times, this word meant “non-Greek speaker” or foreigner, without necessarily carrying the pejorative connotations it later acquired. As Roman influence spread across North Africa, they applied this label to the indigenous tribes they encountered, fierce, independent peoples who resisted assimilation and maintained their distinct cultural identity.

The Romans weren’t the first to interact with these remarkable people. Ancient Egyptians documented encounters with Libyan tribes (early Berber groups) as far back as 3000 BCE. The Greeks established colonies in Cyrenaica (modern-day Libya) and traded extensively with Berber kingdoms. Later, during the medieval period, European cartographers labeled North Africa’s Mediterranean coast as the “Barbary Coast,” directly referencing the Berber populations who inhabited these regions.

In stark contrast, “Amazigh” represents self-identification, how these people have always known themselves. The word embodies core values of freedom, dignity, and nobility that have defined Berber culture throughout history. In the Tamazight language, “Amazigh” (singular) and “Imazighen” (plural) aren’t merely ethnic labels; they’re declarations of independence and pride. A single Amazigh woman is called “Tamazight,” which also happens to be the name of their language, a linguistic coincidence that beautifully illustrates the inseparable connection between identity and tongue.

| The language and also the feminine form of Amazigh | Origin | Meaning | Current Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berber | Greek/Latin | “Barbarian” or foreigner | Common in international contexts; historically dominant |

| Amazigh/Imazighen | Tamazight language | “Free People” or “Noble Men” | Preferred by the people themselves; increasingly used in respectful modern discourse |

| Tamazight | Indigenous | The language and also feminine form of Amazigh | Used to refer to the Berber language family |

Understanding this etymology matters because language shapes perception. When we acknowledge the Amazigh people by their chosen name, we honor their sovereignty and recognize their status as North Africa’s original inhabitants, not as outsiders or “barbarians” in their own homeland.

Where Do the Berbers Live Today? Geographic Distribution Across North Africa

The Amazigh people don’t exist as a monolithic group confined to a single region. Instead, they form a diverse mosaic of communities scattered across North Africa’s vast landscapes, from the Mediterranean coastline to the deep Sahara. Today, an estimated 25 to 35 million Amazigh people maintain their distinct cultural identity across multiple nations, with the largest populations concentrated in Morocco and Algeria.

Morocco: The Berber Heartland

Morocco hosts the largest Amazigh population in the world, with Berber-speaking communities comprising approximately 40-60% of the country’s total population. The history of Berbers in this region runs deep, with distinct tribal groups occupying different geographic zones:

- The Rif Mountains (Northern Morocco): Home to the Rifian Berbers, this rugged Mediterranean coastal range has historically been a bastion of independence. The Rif people speak Tarifit, one of the three major Berber language variants in Morocco.

- Middle Atlas Mountains: This central highland region is primarily inhabited by the Amazigh Zayane and Beni Mguild tribes. The charming cedar forests and traditional Berber villages here offer travelers an authentic glimpse into mountain life.

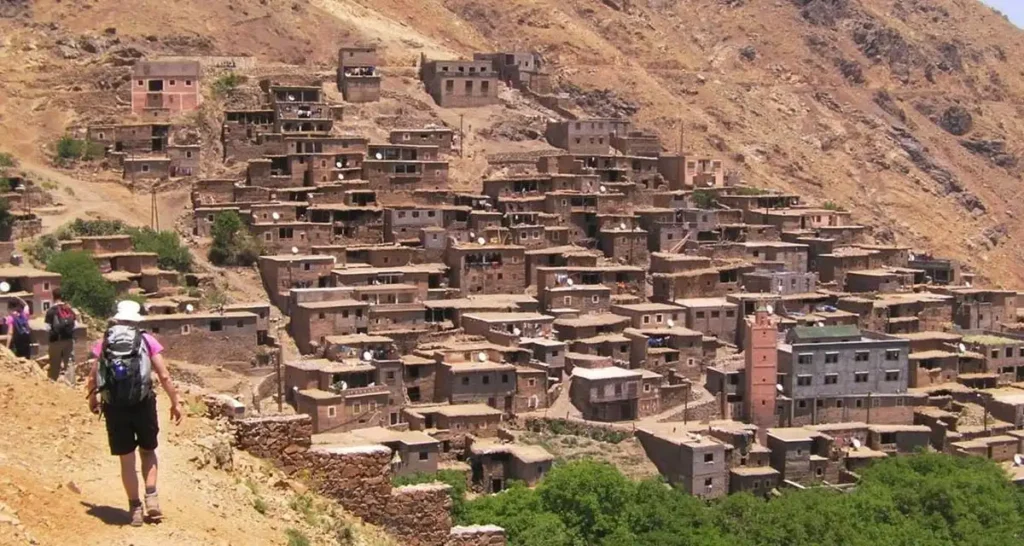

- High Atlas Mountains: Stretching across central Morocco, this dramatic mountain range, including North Africa’s highest peak, Mount Toubkal, is home to Tashelhit-speaking Berbers. Villages cling to mountainsides, and ancient kasbahs dot the valleys.

- Anti-Atlas and Souss Valley: In southern Morocco, the Anti-Atlas region and the fertile Souss Valley host significant Berber populations. The historic city of Taroudant and the coastal city of Agadir serve as cultural centers for the Souss Berbers.

- Pre-Saharan Valleys: The Draa Valley, Dadès Valley, and Todra Gorge regions represent the transition zone between the mountains and the desert, where Berber communities have thrived for millennia as traders and oasis farmers.

Algeria: Kabylie and Beyond

Algeria’s Berber population is estimated at 10-15 million people, with distinct regional groups:

- Kabylie (Greater and Lesser): Located in the northern coastal mountains east of Algiers, Kabylie is the cultural and political heart of Algerian Berber identity. The Kabyle people have been at the forefront of Amazigh rights movements.

- Aurès Mountains: In northeastern Algeria, the Chaoui Berbers have inhabited these highlands since ancient times, maintaining strong cultural traditions despite centuries of external influence.

- M’zab Valley: The Mozabite Berbers of central Algeria have created a unique civilization around seven fortified cities in the Sahara. Their distinctive architecture and social organization have earned UNESCO World Heritage status.

The Sahara: The Tuareg Nation

Perhaps the most romanticized Berber group, the Tuareg people roam the vast Sahara Desert across multiple modern nations, including:

- Southern Algeria, Northern Mali, Niger, and Southern Libya: These “Blue People” (named for their indigo-dyed clothing) maintain semi-nomadic lifestyles, traveling ancient caravan routes that once connected sub-Saharan Africa with Mediterranean markets.

Tunisia, Libya, and the Diaspora

- Tunisia: Berber communities in southern Tunisia, particularly around Matmata and the island of Djerba, preserve unique cultural practices and architecture.

- Libya: The Nafusa Mountains in northwestern Libya host significant Berber populations, while smaller communities exist in other regions.

- Modern Diaspora: Substantial Amazigh communities now live in Europe (particularly France, Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands) and North America, maintaining cultural connections to their ancestral homelands.

For travelers exploring Morocco with Desert Merzouga Tours, encounters with Amazigh people are inevitable and enriching, whether sharing mint tea with a Berber family in the Atlas Mountains, learning about desert survival from Tuareg guides in the Sahara, or shopping in the Berber-run souks of Marrakech.

A Brief History of the Amazigh People: From Ancient Times to Modern Recognition

Pre-Islamic Origins: Ancient Civilizations and Early Kingdoms

The history of Berbers stretches back into prehistory, with archaeological evidence suggesting continuous habitation of North Africa by Berber-speaking peoples for at least 10,000 years. The ancient Egyptians documented interactions with Libyan tribes (proto-Berber groups) as early as the Old Kingdom period (circa 2686-2181 BCE), depicting them in hieroglyphic texts and tomb paintings.

By the 3rd century BCE, Berber civilization had produced sophisticated kingdoms. The most famous was the Kingdom of Numidia (202-46 BCE), which emerged after the Second Punic War. King Masinissa united Berber tribes and created a powerful state that rivaled both Carthage and Rome. His capital, Cirta (modern-day Constantine, Algeria), became a center of learning and culture. Berber nobility adopted Punic writing systems and engaged in Mediterranean trade networks while maintaining their distinct ethnic identity.

The legendary city of Carthage itself, founded by Phoenicians in 814 BCE (in modern-day Tunisia), developed through extensive interaction with indigenous Berber populations. Many historians argue that Carthaginian culture was a hybrid, Phoenician and Berber, and that some of Carthage’s greatest generals, including possibly Hannibal himself, had Berber ancestry.

Another significant Berber kingdom was Mauretania (not to be confused with the modern nation of Mauritania), which extended across northern Morocco and Algeria. King Juba II, a client king of Rome, transformed Mauretania into a center of Hellenistic learning and art during the 1st century CE, proving that Berber rulers could successfully synthesize different cultural influences without abandoning their indigenous identity.

Roman and Arab Conquests: Resistance, Adaptation, and Cultural Synthesis

When Rome conquered North Africa following the destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE, it encountered fierce Berber resistance. For centuries, indigenous people of North Africa alternately fought against and accommodated Roman rule. The Romans built impressive cities across the Maghreb, Leptis Magna, Volubilis, Timgad, many of which were governed by Romanized Berber elites who adopted the Latin language and customs while maintaining connections to their tribal heritage.

Berber culture significantly influenced Roman North Africa. Septimius Severus, Roman Emperor from 193-211 CE, was of Berber-Punic ancestry from Leptis Magna (in modern Libya). Saint Augustine of Hippo, one of Christianity’s most influential theologians, was a Berber from Numidia. These examples illustrate how the Amazigh people didn’t simply absorb Roman culture; they helped shape it.

The most dramatic transformation in Berber history came with the Arab-Islamic conquest of the 7th-8th centuries CE. Unlike previous invasions, this wasn’t merely a military conquest but also a religious and linguistic revolution. Arab armies swept across North Africa between 647-709 CE, encountering determined Berber resistance led by legendary figures such as Queen Dihya (also known as al-Kahina), a Berber warrior queen who fought Arab expansion in the Aurès Mountains.

Despite initial resistance, most Berber populations eventually converted to Islam, though the process took several centuries and was far from uniform. Importantly, conversion to Islam didn’t mean abandonment of Berber identity. Instead, the Amazigh people created their own interpretations of Islamic practice, often blending it with pre-Islamic traditions. Many Berbers adopted Kharijite Islam, a sect emphasizing egalitarianism and resistance to centralized authority, values that resonated with tribal Berber society.

Berber dynasties would subsequently dominate North African and Iberian history for centuries. The Almoravid Dynasty (1040-1147), originating from Saharan Berber tribes, conquered Morocco and much of Spain. The Almohad Dynasty (1121-1269), another Berber movement, extended even further, ruling from Libya to Portugal. The Marinid Dynasty (1244-1465) established Fes as a major center of Islamic learning. These powerful Berber empires demonstrated that the Amazigh people were not merely subjects of history but its makers.

Colonial Period: Suppression and Survival

European colonization, French in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia; Spanish in northern Morocco; Italian in Libya, brought new challenges to Berber identity. Colonial powers often implemented “divide and rule” policies, sometimes favoring Berber groups over Arabs or vice versa, attempting to fragment North African solidarity. The French notably created the “Berber Dahir” in Morocco (1930), which tried to separate Berber legal systems from Islamic law, sparking widespread protests.

During colonial resistance movements, Berbers played crucial roles. Abd el-Krim led the Rif War (1921-1926) against Spanish and French forces in northern Morocco, creating the Republic of the Rif, one of the first modern republics in the Arab world. His guerrilla tactics influenced later anti-colonial movements globally.

Modern Era: The Fight for Recognition and Language Rights

Post-independence, many North African nations pursued “Arabization” policies that marginalized Berber culture and language. In Algeria, Morocco, and Libya, Tamazight was excluded from official education, government, and media. This sparked the Berber Cultural Movement, particularly strong in Algeria’s Kabylie region, where protests in the 1980s (the “Berber Spring”) demanded recognition of Amazigh identity.

Progress has been gradual but significant:

- Morocco (2011): Tamazight became an official language alongside Arabic in the new constitution, following decades of Amazigh activism.

- Algeria (2016): Tamazight gained official language status, recognizing the rights of Algeria’s substantial Berber population.

- Libya: The post-Gaddafi period has seen renewed Amazigh cultural expression, though political instability complicates progress.

Today, who are the Berbers in the modern world? They’re doctors, teachers, artists, athletes, and political leaders who maintain their ancestral identity while fully participating in contemporary society. The Amazigh flag, featuring blue, green, and yellow stripes with a red Yaz (ⵣ) symbol, flies proudly at cultural events, symbolizing the resilience of a people who have survived millennia of change without losing their essential character.

Berber Culture and Traditions: The Living Heritage of the Amazigh

Understanding Berber culture means recognizing a living tradition that has evolved over millennia while maintaining core characteristics. For travelers exploring Morocco, these cultural elements aren’t museum pieces; they’re the fabric of daily life in countless villages and communities.

Language: Tamazight and the Ancient Tifinagh Script

The Tamazight language represents the soul of Amazigh identity. Technically, “Tamazight” encompasses multiple related Berber languages and dialects across North Africa, forming part of the Afro-Asiatic language family (which also includes Arabic, Hebrew, and ancient Egyptian). The three major variants in Morocco are:

- Tarifit (Rif Mountains)

- Tamazight (Central Morocco and Middle Atlas)

- Tashelhit (High Atlas, Anti-Atlas, and Souss)

While mutually intelligible to varying degrees, these variants have distinct vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammar. The standardization efforts of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in Morocco have created “Standard Moroccan Amazigh” for educational purposes.

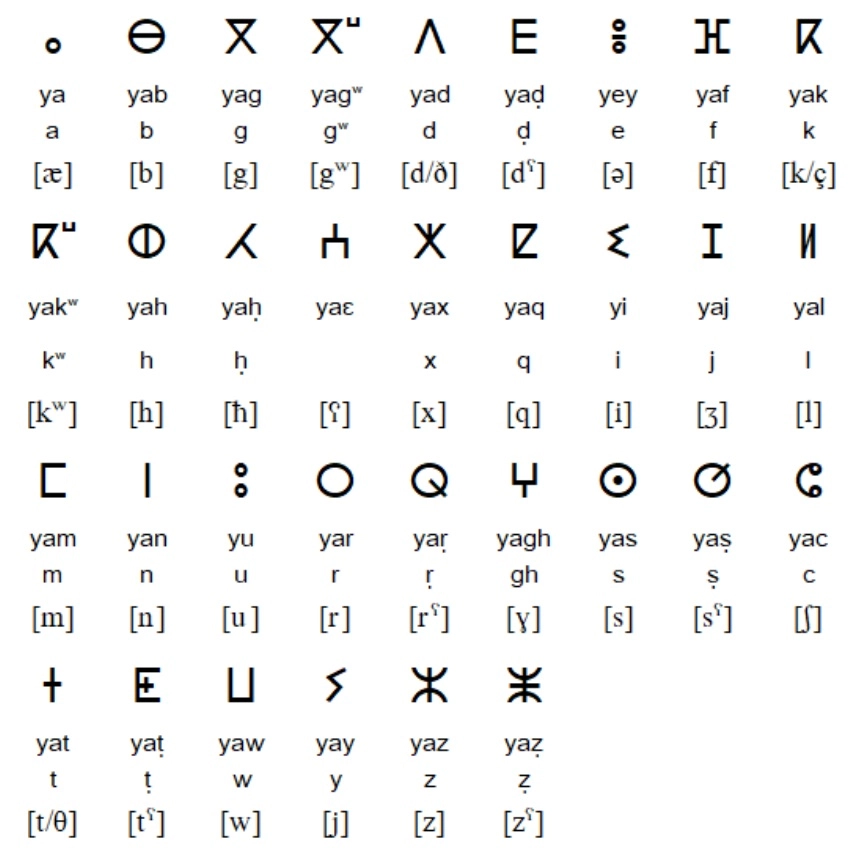

What makes Tamazight truly unique is Tifinagh, the indigenous Berber alphabet. These geometric characters, resembling abstract symbols more than conventional letters, date back at least 2,500 years, with variants used by ancient Numidian kingdoms and still employed by Tuareg communities today. The modern Neo-Tifinagh script, revived and standardized in the 20th century, appears on Moroccan road signs, official documents, and banknotes—a visible symbol of cultural recognition.

Sample Tifinagh characters (ⴰ ⴱ ⴳ ⴷ) carry profound historical weight. For Berbers, Tifinagh isn’t merely a writing system; it’s a link to ancestors who carved these symbols into rocks across the Sahara, a declaration that Amazigh civilization predates Arab and European presence by millennia.

Religion: From Ancient Beliefs to Modern Islam

Pre-Islamic Berber spirituality was complex and varied, incorporating animistic beliefs, ancestor worship, and recognition of natural forces. Some Berber groups worshipped the sun, moon, and earth. The Guanche people of the Canary Islands (considered Berber descendants) mummified their dead, suggesting possible ancient Egyptian influence or parallel development.

When Christianity spread through the Roman Empire, many Berbers converted, producing influential Christian theologians and martyrs. However, Christianity in North Africa was largely swept away by Islam.

Today, the overwhelming majority of Berbers practice Sunni Islam, primarily following the Maliki school of jurisprudence. However, Berber Islam often incorporates distinctive elements:

- Maraboutism: Veneration of local saints (marabouts) and visits to their tombs (often white-domed shrines dotting the Moroccan landscape) blend Islamic and pre-Islamic traditions.

- Seasonal celebrations: Many Berber communities maintain agricultural festivals that predate Islam.

- Spiritual practices: Certain Berber groups preserve folk beliefs about jinn (spirits), the evil eye, and healing practices that exist alongside orthodox Islamic observance.

The Berber approach to religion reflects their historical pattern: accepting new influences while maintaining distinct cultural practices.

Social Structure: Tribes, Community, and the Status of Women

Traditional Berber society was organized around tribal confederations (taqbilt in Tamazight), with each tribe comprising multiple clans and extended families. These weren’t simply administrative units; they were the foundation of Berber identity, law, and social organization.

Decision-making in many Berber communities traditionally involved the jama’a (village assembly), a democratic council of male elders who resolved disputes, managed resources, and made collective decisions. This egalitarian impulse distinguished Berber governance from more hierarchical Arab systems.

One of the most remarkable aspects of Berber culture is the relatively high status of women compared to many other traditional societies. While patriarchal elements certainly exist, Berber women have historically enjoyed more freedoms than their Arab counterparts:

- Property rights: Berber women could own and inherit property independently.

- Economic participation: Women actively engaged in agriculture, craft production (particularly weaving and pottery), and trade.

- Social freedom: In many Berber communities, women didn’t practice strict veiling and participated in public life more openly.

- Matrilineal elements: Some Berber groups, particularly the Tuareg, show matrilineal tendencies, with property and lineage passing through female lines.

The legendary Berber warrior queens—such as Dihya (al-Kahina), who led resistance against Arab conquest, and Tin Hinan, the semi-mythical Tuareg matriarch—exemplify how Berber culture has historically allowed space for female power and autonomy.

Arts and Crafts: Visual Expression of Identity

Berber carpets and textiles are world-renowned for their geometric patterns, vibrant colors, and symbolic motifs. Each region produces distinctive styles, Beni Ourain rugs from the Middle Atlas with their minimalist black symbols on white wool, colorful Boucherouite rag rugs from southern Morocco, or the intricate Tazenakht kilims. These aren’t merely decorative objects; they’re narratives woven into wool, with symbols representing fertility, protection, femininity, and tribal identity.

Jewelry and silver work constitute another major Berber art form. Traditional Amazigh jewelry features bold geometric designs, often incorporating coral, amber, and enamel alongside silver. The fibula (large decorative pins) and khamsa (hand-shaped amulets) carry both aesthetic and protective functions.

Music and dance vary across Berber regions but share certain characteristics, rhythmic drumming, call-and-response vocals, and collective participation. The Ahwash dance of the High Atlas, where men and women form concentric circles and perform synchronized movements to poetry and percussion, exemplifies the communal nature of Berber performing arts.

Culinary Traditions: The Berber Kitchen

While Moroccan cuisine is celebrated globally, many of its signature dishes have Berber origins:

- Tagine: The conical clay pot and slow-cooking technique are authentically Berber, predating Arab influence.

- Couscous: This grain staple is considered a Berber invention, with Friday couscous remaining a sacred tradition in many North African homes.

- Berber bread: Baked in traditional clay ovens or buried in desert sand.

- Preserved foods: Smen (fermented butter) and various dried vegetables reflect nomadic and mountain lifestyles where food preservation was essential.

Mint tea (atai in Berber dialect), while likely introduced to Morocco via British trade, has become central to Berber hospitality. The elaborate tea ceremony, the pouring from heights to create foam, represents welcome, friendship, and the sacred duty of hospitality that pervades Berber culture.

10 Fast Facts About the Berber People

- They Have Their Own Calendar: The Berber calendar (Yennayer) begins in 950 BCE, marking the date when Shoshenq I, a Berber pharaoh, ascended to the Egyptian throne. Berber New Year falls around January 12-14 and is celebrated with special foods and festivities.

- Famous Tea Culture: The elaborate Moroccan mint tea ceremony is integral to Berber hospitality. Refusing tea can be considered rude, and the ritual involves three pourings, each with symbolic meaning: the first is “gentle as life,” the second “strong as love,” and the third “bitter as death.”

- Celebrity Berber Descendants: Legendary French footballer Zinedine Zidane has Berber (Kabyle) roots from Algeria. Other notable figures include Saint Augustine, Roman Emperor Septimius Severus, and fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent (who deeply loved Berber culture).

- The Tuareg are “Blue People”: Tuareg men wear indigo-dyed tagelmust (turbans) that often stain their skin blue, earning them the nickname “Blue Men of the Desert.” In Tuareg society, men, not women, traditionally cover their faces.

- Ancient Rock Art: The Sahara Desert contains thousands of rock engravings and paintings created by ancient Berbers, depicting extinct wildlife like elephants and giraffes, proving the Sahara was once verdant.

- Gender-Reversed Literacy: Among the Tuareg, women have historically had higher literacy rates than men, as they’re the primary transmitters of Tifinagh script and cultural knowledge, an inversion of most traditional societies.

- Berber Dynasties Ruled Spain: The Almoravids and Almohads, powerful Berber empires, controlled medieval Spain (Al-Andalus), leaving architectural masterpieces like the Giralda in Seville and the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech.

- Matrilineal Tuareg: Tuareg society traces descent through maternal lines, and women don’t veil their faces, both unusual practices in the broader Islamic world and reflections of pre-Islamic Berber customs.

- Resilient Language: Despite centuries of Arabization, an estimated 25-35 million people still speak Tamazight languages today, making it one of the world’s oldest surviving language families.

- UNESCO-Recognized Heritage: Numerous Berber sites are UNESCO World Heritage Sites, including the M’zab Valley’s fortified cities, the Ksar of Aït Benhaddou (featured in films like Gladiator and Game of Thrones), and the ancient city of Volubilis.

Experiencing Berber Culture: A Traveler’s Perspective

For visitors to Morocco, engaging with Berber culture isn’t an optional add-on; it’s fundamental to understanding the country’s identity. The Atlas Mountains, the Sahara Desert, and countless villages offer authentic opportunities to experience Amazigh hospitality, traditions, and daily life.

A journey through Berber Morocco might include:

- Mountain trekking through High Atlas villages where traditional lifestyles persist, staying in family-run gîtes where you’ll share meals and stories.

- Desert camping with Tuareg or southern Berber guides who navigate by stars and share oral histories passed down through generations.

- Market visits to souks where Berber women sell handwoven carpets, pottery, and argan oil, providing income that sustains traditional crafts.

- Culinary experiences preparing tagine or couscous in a Berber home, learning techniques refined over centuries.

- Architectural exploration of kasbahs, ksour (fortified villages), and agadirs (collective granaries) that showcase Berber engineering adapted to harsh environments.

When you share tea with a Berber family, purchase a handwoven carpet, or listen to drumming echoing through mountain valleys, you’re not consuming culture as a tourist commodity; you’re participating in a living tradition that has survived empires, religions, and modernization.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Berber People

What race are Berbers?

The Amazigh people are ethnically distinct from Arabs, though the concept of “race” is scientifically problematic and often misleading.

Genetically, Berbers are indigenous North Africans with ancient roots in the region predating Arab, Roman, and Phoenician arrivals. Genetic studies show they share ancestry with ancient populations of North Africa and the Mediterranean basin. Physical appearance varies considerably; some Berbers have darker skin and African features, particularly in Saharan regions, while others have lighter skin and European features, especially in mountain areas.

This diversity reflects millennia of North Africa’s position as a crossroads of human migration. What unites Berbers isn’t physical appearance but shared linguistic heritage, cultural practices, and self-identification as Amazigh.

What language do Berbers speak?

Berbers speak Tamazight, an umbrella term for a family of related Afro-Asiatic languages. In Morocco alone, the three major variants are Tarifit (northern Morocco), Central Atlas Tamazight (Middle Atlas), and Tashelhit (southern Morocco and High Atlas). These variants are somewhat mutually intelligible but have distinct features. The Tuareg people speak Tamashaq. Written Berber uses the Tifinagh script, an ancient alphabet that predates Arabic script in North Africa. Since Morocco’s 2011 constitution, Tamazight has been an official language alongside Arabic, appearing on road signs, currency, and government documents. However, Arabic remains dominant in urban areas and formal education, while Berber languages are primarily spoken in rural communities and at home.

Are Berbers Arab?

No, Berbers are not Arab; they are a distinct ethnic group indigenous to North Africa who predate the Arab arrival by thousands of years. The confusion arises because most Berbers today are Muslim and many speak Arabic in addition to or instead of Tamazight, particularly in urban areas.

The Arab conquest of North Africa (7th-8th centuries CE) brought Islam and the Arabic language, and subsequent centuries saw varying degrees of Arabization. However, Arab identity is primarily linguistic and cultural, while Berber identity is ethnic and historical. Many North Africans today have mixed Arab-Berber heritage, but the Amazigh people maintain a distinct identity, language, and cultural traditions separate from Arab culture.

The modern Berber cultural movement actively emphasizes this distinction, advocating for Amazigh language rights and cultural recognition distinct from Arab identity.

Where can I experience authentic Berber culture in Morocco?

Authentic Berber experiences are found throughout Morocco, particularly in rural areas. The High Atlas Mountains offer numerous Berber villages accessible via trekking routes, where families operate guesthouses providing meals and accommodation. The Dadès and Todra Valleys showcase stunning Berber kasbahs and traditional architecture. The village of Aït Benhaddou, though touristy, remains a functioning ksar with Berber families still residing there.

For desert culture, Tuareg and southern Berber communities in the Erg Chebbi dunes near Merzouga offer camel treks and desert camps with authentic cultural experiences. The markets (souks) in smaller towns like Azrou, Midelt, or Tinerhir provide more genuine interactions than large city souks. When traveling with reputable tour operators like Desert Merzouga Tours, guides can facilitate meaningful cultural exchanges, sharing tea with families, visiting cooperative workshops, or participating in traditional activities, which transform a tourist visit into cultural immersion.

What is the significance of Berber carpets?

Berber carpets are far more than floor coverings; they’re visual languages encoding cultural identity, family history, and spiritual beliefs. Each tribe and region produces distinctive styles with specific motifs: diamonds representing femininity and the evil eye, crosses symbolizing faith or stars, zigzags depicting water or mountains. Traditionally, Berber women weave carpets as part of their dowry, documenting their lives through abstract symbols.

The Beni Ourain carpets with minimalist black symbols on cream wool have become fashionable in Western interior design, but originally, each mark told a story. Colors carry meaning too: red for strength and protection, blue for wisdom, green for peace, and yellow for eternity. When you purchase an authentic Berber carpet, you’re acquiring a piece of functional art that required weeks or months of work and carries centuries of cultural continuity. Many women’s cooperatives now produce carpets, providing crucial income while preserving traditional skills threatened by mass production.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Amazigh People

Who are the Berbers? They are North Africa’s indigenous people, the original inhabitants of vast territories from the Atlantic to the Nile, from the Mediterranean to the Sahara. They are the descendants of ancient kingdoms that traded with the Phoenicians, resisted the Romans, converted to Islam while maintaining a distinct identity, built empires that ruled medieval Spain, and survived colonialism with their culture intact.

The history of Berbers is a testament to cultural resilience, the ability to absorb influences from Phoenicians, Romans, Arabs, and Europeans without disappearing into those cultures. Today’s Amazigh people are doctors and farmers, urban professionals and mountain shepherds, contemporary artists and traditional craftspeople. They speak multiple languages, navigate modern and traditional worlds, and increasingly assert their identity in Morocco’s political and cultural landscape.

For travelers, understanding Berber culture enriches every Moroccan experience. The landscapes that captivate visitors, the Atlas Mountains, Sahara dunes, ancient kasbahs, and vibrant souks, are Amazigh homelands where this culture continues to thrive. When you trek mountain trails, you follow paths carved by Berber shepherds over millennia. When you sleep in desert camps, you experience hospitality traditions as old as the stars used for navigation. When you admire hand-woven carpets or share mint tea, you participate in customs that connect the present to the distant past.

The Amazigh people ask for recognition, not pity; respect, not romanticism. They are not relics of history but vital contributors to contemporary North African society. Their language rights struggles mirror indigenous movements worldwide. Their cultural contributions, from ancient kingdoms to modern activism, deserve celebration beyond tourist stereotypes of exotic nomads or picturesque mountain dwellers.

As Morocco continues modernizing, the question of how to preserve Berber culture while embracing progress remains crucial. UNESCO recognition, constitutional language rights, and cultural institutes represent important steps. But perhaps the most powerful preservation happens in everyday moments: children learning Tifinagh in school, families speaking Tamazight at home, women weaving traditional patterns, musicians playing ancient rhythms, and elders sharing oral histories.

When you travel to Morocco, you’re entering a land where the indigenous people of North Africa still live, work, and shape their destiny. The Berbers, the Amazigh, the Free People, invite you not merely to visit their homeland but to understand and respect the remarkable civilization they’ve maintained across millennia. In doing so, you become part of a story thousands of years old, still being written by the Imazighen today.

Ready to experience authentic Berber culture firsthand? Desert Merzouga Tours offers customized journeys through Morocco’s Berber heartland, from the High Atlas Mountains to the Sahara Desert. Our expert local guides, many of Berber heritage, provide genuine cultural immersion, from family-hosted meals to overnight stays in traditional Berber villages. Contact us to design your personalized Moroccan adventure that honors and celebrates the enduring legacy of the Amazigh people.